Life at the Docks , By a Dock Labourer

Chapter I, THE DOCKS

To a Liverpool reader it is hardly necessary to describe the Liverpool Docks, though to the stranger and far-off resident they embody something enormous and magnificent. And so in reality they are, stretching for fully 6 miles along the eastern bank of the river Mersey, they present a solid and massive front to the tidal waves, a front unbroken except by the various gates and entrances through which the shipping gains admission to the inner docks. Built with a light coloured granite material, and adorned here and there with turrets of handsome and varied outline, the whole presents a front agreeable to the eye, and in pleasing contrast to the dingy, dilapidated wharves of London and New York.

But the docks themselves are triumphs of Masonic art. The hard stone facings are dove-tailed and interlocked so completely as apparently to defy the action of wind and water for ages to come, and one could hardly suppose the combined attack of the whole British fleet, with the aid of every 81ton gun in the British armoury, would have the slightest effect upon the solid masonry. Huge folding gates, worked by powerful chain cables running over massive rollers, and operated upon by hydraulic power, open and close with the regularity of the tides and admit all sorts and conditions of craft, from the humble Runcorn flat or barge to the stately Atlantic steamer. The Mersey itself, broad, sparking and brilliant on the surface, is a villainous tributary at bottom. Treacherous and shifty, its sands are always on the move, and at low-water deeply laden vessels have to lie in the river until lightened of sufficient cargo to permit them floating safely into their respective docks. The new northern docks, however, have been specially constructed at a point in the river favourable to deep entrances where even the leviathans of the deep may find refuge at any state of the tide during high water, and the expense attended "lightening" cargo inwards or outwards avoided.

But if the docks themselves, their construction, appliances, and enormous cargo sheds, their wet and dry appendages for the repair of vessels, and their vast area and extent, be objects of admiration and wonder, what must be the feeling prompted by even a cursory survey of the innumerable products, animal, vegetable and mineral, of every country on the face of the globe, which are here, displayed daily, poured forth from the holds of scores upon scores of brigs, schooners, barques, ships and steamers? Beginning at the extreme north, at the new docks devoted to the Atlantic trade, we may see here any day enormous piles of wheat from Chicago, bacon from Cincinnati, cotton from Pennsylvania, tobacco from Virginia and Baltimore, corn, leather, lard, cheese, staves, tallow, treacle, butter and manufactured goods, from pitchforks to clothes-pegs, from perambulators to pianos. Further south at the Huskisson, Sandon and Nelson Docks may be seen the luscious fruits of the Mediterranean, the oranges of Seville, the wines of Portugal, the mohair of Syria, the gum of Arabia, the opium and castor oil of Calcutta, the tobacco and cigars of Manilla, together with the sugar and rum of Jamaica, the India-rubber of Pars, the logwood of Hayti, and the coffee of Cuba. Again, the Victoria, Waterloo and other docks disclose to us the grand staple of Liverpool commerce, the strength of Lancashire, and the sport of speculators, the cotton of the United States. The Clarence and Trafalgar docks are chiefly devoted to the Irish and Scotch coasting trades, and here the political or social philosopher may reflect that during the past 40 years a mournful procession of two and a half millions of Irish exiles has wended its sad journey over these stones in search of fresh fields and new homes where the crowbars cease to trouble and the bailiff is at rest. Continuing our survey along the line, we come to the miscellaneous docks, where we discover all sorts of importations, from Welsh slate to paving stones, beeswax, borax, Egyptian cotton, and Bombay cotton, and Sea Island cotton, sulphur, sumac, hemp, and hickory, pitchpine, oak, mahogany, maple, walnut, and all the finer descriptions of wood, to say nothing of the endless variety of useful and superfluous articles, too numerous to mention, from the craved idol in ivory of Japan to the ready-made doors and window frames, and even coffins of Boston and New York.

But Liverpool is merely the mouth into which all these good, bad, and indifferent commodities are put. In the body geographical, the various railways and canals are the veins and arteries through which they are transmitted, and Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, and other large towns, with innumerable smaller villages and districts throughout the country, are the stomachs which digest and assimate the whole, not indeed the whole, but all that is left after a certain proportion is transhipped to France, Belgium and other countries. This, then, may represent a summary of the import trade of the far-famed city whose ships traverse all waters and penetrate to every clime, whose hardy sailors have done battle with the storms and the tempests of the fierce Atlantic, or broiled beneath the heat of a tropical sun, and whose name and renown are as household words in every port in the civilised world, from Yokohama to New Orleans, Honk Kong to San Francisco.

Chapter 11, Working at the Docks

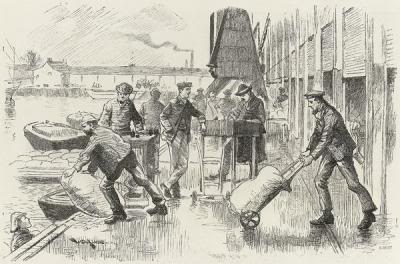

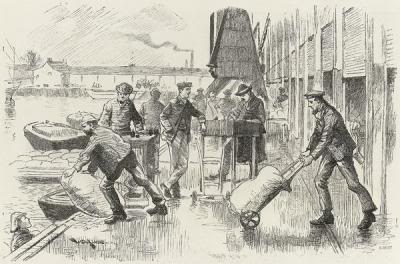

"Working at the Docks" is a comprehensive term. It embraces a large variety of labour, both mental and manual, and no small amount of dexterity and skill. Even a dock labourer to be of any use at all, must have some little training. The mere possession of a "hook" and the physical ability to push or pull a heavy laden truck do not make an accomplished dock labourer. To be an expert in the craft it is necessary that a man should have some knowledge of the nature and properties as well as the outward appearance of the thousand-and-one articles of produce discharged daily from ships of every clime in the world, and not only this but he must be able to "weigh", "lot", "mark", "select", "stow", "sample", and "trim" every package coming under his hands and know how to "bushel" and carry grain into the bargain. Should he aspire to the higher branch of his profession, and become a "stevedore" or "lumper" at 5s a day, he must know how to load a ship, to nicely discriminate the relative weight, size, fragility, and composition of every conceivable commodity, so as to stow them safely and economically in the ship's hold, with due regard to the fact that gunpowder and lucifer matches are ugly neighbours, that pig iron is a heavy nightmare upon Manchester fine goods, and Irish whisky or paraffin oil undesirable in the neighbourhood of the coal bunkers.

Dock labourers are divided into two distinct classes, the lumpers, who discharge cargo from the ship's hold, and, second the porters who receive the cargo after landing, and weigh, mark, stow, and load off the same. Stevedore's are men who load outward cargo, but they also act as lumpers, and for practical purposes, one class can and do perform the other's work. The porters are paid in Liverpool at the rate of 4s-6d per day, and the lumpers and stevedores at 5s per day, of nine hours. In order to protect cargo, and facilitate its loading and discharge, and to enforce such regulations and scales of payment as may be found equitable as between shipowners and consignees, the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board issue, under act of Parliament, licenses to certain persons called Master Stevedores and Master Porters, authorising them to act in accordance with certain specified rules, and to levy certain fixed rates on all goods handled by them, in loading or discharging vessels. Any man of good character and who can give the necessary bond, may obtain a master stevedore's license, and begin business at once, provided he gets any business to do. He needs little capital to commence with, as he may, at any time obtain advances from his employer, the shipowner, sufficient to pay his wages, which is about all the outlay he, as a beginner, has to make. The master porter on the other hand, must have some capital, and a few "traps" to start with. His paymasters are the various consignees of inward cargo, upon whom he makes his charges according to a fixed rate, and from whom he collects his bills as best he can from time to time a mutual convenience. But there is one qualification indispensable to both alike, and that is the faculty of being able to squeeze as much as possible out of the labourers and get through the most "tonnage" in the day's operations that can be obtained.

Dock labouring is at all times a precarious and uncertain mode of living. The supply of workmen in Liverpool always greatly exceeds the demand and the consequence is that the average earnings the year round do not exceed four days, or 18s per week. At the permanent berths of all the large steamship companies, however, there is what may be called a regular staff of constantly employed men, not exceeding perhaps about twenty men each firm, whose wages vary from 24 to 30s per week and whose duties are chiefly clerical, such as freight clerks, weight-takers, who book the weights at the scales, "counters off" who count or tally off the packages of goods on delivery and take receipts for the same, and checkers who check the operations of the counter off. To these may be added the "boss" stevedores and the "boss" porters, whose main qualifications are the ability to work the hatches with the smallest number of men, to possess thundering voices, strong coercive and combative powers, some judicious swearing talents, and a nicely-balanced faculty for imbibing a goodly share of WALKER'S and CAIN'S six-penny when the happy occasion offers. These constitute the working or outdoor staff of the master porter, and considering the amount of work got through the important and often dangerous and delicate nature of it, the wages they receive are modest enough.

As to the rank and file, the life is miserable, and laborious. Let us see if we can sketch what may be witnessed any morning on the "stands" along the line of docks at about 7am. Here at various shed entrances may be seen a "ring" of from 100 to 200 men, of all sorts and conditions, varying in height, age, and nationality, and uniform in only the common desire to get work if possible. Here is a scantily-dressed young man pale and anxious eyed, evidently has "seen better days" probably some poor city clerk, suggestive of billiards and latch keys, has just invested his last 3d in a second-hand cotton hook, and now he is waiting his chance. There, immediately behind him stands a tall, good-looking man, a man of muscle and moustache, who was 7yrs in the police force but got "sacked for something" and now he is on a fresh beat for work. Over in yonder corner stands a fair-haired freckled son of Erin, shy and abashed, in the midst of the big crowd, fresh from the green and shamrocked sod of Galway. This is the poor boy's first venture in the dock quays, and he is fain to exchange the familiar reaping hook of his native land for the cotton hook of the Saxon. The broken down tradesman, the deserted soldier, the unsuccessful student, the ruined clerk, the brandy-visaged barman, and the betting man too heavily handicapped in the race of life, all come here at last, struggling and striving, pushing and praying, cursing and crowding round the stand, to "get a few days at the docks!"

Chapter III, The Dock Labourer's home.

As may well be imagined the dock labourer's home is a poor one. House-rent in Liverpool is high, much higher than in any town or city in England, except London, and labourer's dwellings are about the worst in the kingdom. Taking at random, a typical street leading off Vauxhall Rd, we have a fair sample of a dock labourer's "home" This is a long narrow street, flanked at either end, at the corners, and fortified at many other intersecting corners throughout its length by showy public-houses. Each side of the street at short intervals, discloses a court or narrow alley, the first prominent feature of which is a pair of water-closets, abutting in the foreground like two unsavoury gate pillars, beyond which is seen a double row of from 6 to 8 houses, facing each other so closely that a whispered conversation may easily be carried across from door to door. Below are the battered remains of what was once a flagged pavement, filthy and repulsive, above a narrow strip of blue sky, disclosing the only bit of genuine colour visible around except what may be seen in the glass barrel of the beerhouse over the way. A house in this court contains four rooms, "straight up and down", no back doors nor windows, for immediately against it stands another similar house in the next court, and the rent is 4s a week, "free of taxes", about the only objectionable thing it is free of, but it may be added that it is also "free" of fresh air, free of drainage, free of cleanliness, free of wholesome wall paper or whitewash, free of sweetness or light or comfort, free, in short of everything which goes to make up a happy or comfortable home. The lower room of this house is a cellar, with one door and one window, one perennially damp floor, and one ceiling level with the flags outside. This apartment is generally "let off" for the poor labourer cannot always afford an entire house to himself, although of late years the authorities have largely put a stop to the practise of sleeping in these caverns, as far as they could do so. The next room above is the kitchen, parlour, and sitting-room in one. Three stone steps from the outside take you straight into it, and the only difference between it and the cellar below is that it is somewhat higher in the walls, has a larger window and more light, and it is furnished with an appendage at the fireplace, called by courtesy a cooking range, but whose capacity in that line would be well tested by anything larger than a rabbit or a 2lb loaf. From this room springs, or rather leans a narrow dilapidated stairs to the top room or garret, the smallest, though perhaps the sweetest room in the house, from its nearness to the fresh air outside, which happily penetrates through the slates above, and gives a purer ventilation than can be got in the stuffy regions below.

This then is the house and these the surroundings where the dock labourer dwells. His furniture is simple and primitive. A round deal table with three legs, two or three chairs, of various build and design, a couple of stools, a dresser for the few plates and dishes required, and a few soiled prints on the wall, these in the kitchen, with one shaky four-poster and a few wretched mattresses in the rooms above, constitute all in the world that the poor man possesses in the shape of household goods. Here he and his wife live and his children are born and reared week-in, week-out, for year end to year end, where the sun never shines, nor the fresh breezes blow, nor the wild birds sings, nor the flower smiles, but where instead malarious gases and foul atmospheres permeate every room, and cut of day by day and month by month victim after victim of the children of toil.

But the homes of the labourer, poor and unwholesome as it generally is, is not always a wretched one. Even in these dismal courts may be occasionally found a happy little home, brightened by a smart tidy little wife and a sober, studious husband, who, after his day at the docks, takes home his Echo or Express and reads it at his own fireside, or helps his children learn their morning school lessons. And it must be borne in mind that the dock labourer as a rule, steady or otherwise, and generally, "otherwise" is a great politician and strong party man.

Many a sound and unsound argument may be heard around the scales as the cargo comes tumbling out, and as each bale of cotton crashes down upon the scale bottom the marker comes down oratorically with a still greater crash upon, Beaconsfield, Salisbury or Sandon, after which the weigher with great emphasis retorts with great effect upon Gladstone, Bright or Forster, as the case may be. In these days of penny and a halfpenny newspapers, every man who can read is bound to know something of the stirring events of the times if he is at all to keep abreast of them, and the dock labourer feels himself as well entitled to discuss the affairs of State on the dock quays or in the hold of a ship as the merchant on Change or the editor in his sanctum.

Chapter IV, The coming Dock Labourer

Amongst the unrecorded achievements of mankind in its early childhood, the acquirement of the alphabet stands foremost. The little urchin who at the age of 6 masters that cabalistic arrangement of curves and lines and angles and actually learns the alphabet backwards and forwards, downwards and across the middle, has accomplished a task that at his age, infinitely surpasses that of the grown man who makes wooden nutmegs or "corners" the cotton market in after life. Still the lad gets no monument. That alphabet comes to him simply as the measles or the whooping cough, and is a mere incident of his life, providentially attacking him early, and leaving no disagreeable reminiscences of the mental torture it must have inflicted on him at the time. But the alphabet nowadays is as inevitable as vaccination, the School Board as exacting as the Board of Health. Every boy and girl must attend school between the ages of 5 and 14, or must reach a certain standard of proficiency before they are excused. This rule is rigorously enforced in Liverpool, and whilst heartily approving of its tendency, it may be worth while to speculate for a few moments upon its ultimate effect upon dock and other labourers.

In the ups and downs of life, and especially Liverpool life, it frequently happens that men of superior mental attainments are compelled for a time to betake themselves to the docks for a living, as an alternative to the workhouse or to that other magisterial "dock" in Dale St, in which the social pirates of the city are finally compelled to moor. Indeed within the writer's experience he has known more than one clergyman, three doctors of medicine, at least one solicitor, and one ex-lieutenant of infantry as dock labourers, and it is no exaggeration to assert that at this moment at least a dozen university men might be found here and there along the lines of the docks pushing the truck or plying the cotton hook, with more earnestness, though perhaps less success than in happier days they translated Horace or solved quadratics.

But this class of men invariably makes bad dock men. Their antecedents tell against them, both physically and mentally, and they never succeed in attaining the easier position of freight clerk or counter off. Naturally discontented they have no ambition in their line of life. Bodily they are unfit for it, partly from their early bringing up, but chiefly from the fact that the arch-demon drink has laid fast hold of them, and refuses to relax one jot of its fatal grip until death mercifully closes the struggle. These unfortunate men turn up and again suddenly disappear, from time to time, on the dock quays of Liverpool, like bubbles of sparkling water on the surface of a stagnant pool. Whence they come, no one knows but themselves, where they go, no one cares, except, perhaps , weeping wives in distant cities, or hapless children who will never again know a father's love or a father's care. Refined education and hard manual labour are apparently incompatible. Nowadays the fairly-educated children are not raised for dock labourers. They are taught to look forward to clerkships or other genteel modes of life, in which, if they subsist poorer, they may at least dress better than as manual labourers. In another decade all our young working men will be masters of the three R's, in 10 years further our labourers on the dock quays may talk Latin, know Euclid, be familiar with Darwin excel in electricity, be great in geology, that is to say if they are content to labour at all, in which event the problem will be, who will work our ships or stow our cargo, or, for the matter of that, who will dig our coals, make our railways, drive our cabs, sail our vessels, black our boots, or even print our newspapers. On the other hand when a good English education becomes so common it will cease to be valuable in the sense that the supply will be much greater than the demand, and its money value as an accomplishment be much less than it is now. If every schoolboy, the child of every dock labourer in Liverpool, be turned out from school at the age of 14 able to keep books by double entry, to work decimal fractions, to measure timber and write a good letter in a good hand, the great army of clerks will be vastly augmented, and the certain consequence of the glut in the market will be less wages and less chance of employment. It will then be found the cotton hook commands better wages than the pen, dock labouring will still flourish, only with a better more intelligent class of men, until such a time may arrive that the shipowner will be able any morning to come down to this place of business and pick out from the "ring" so many men for the main hatch, so many for the fore hatch, so many for his general office and so many for his counting house, each gang proceeding to the sphere of its labours, and each so well up in the others duties that they may exchange places at any time without in any way interrupting the ordinary course of business.

Such may or may not be a correct forecast of the position of affairs in the Liverpool labour market a generation hence, but at all events we may expect under the operation of the School Board, greater general intelligence, more mental capacity, and it is hoped, a much higher moral standard than has yet been attained by the great body of dock labourers.

Chapter V, The Dock Labourer's recreations

A few years ago on the occasion of a "christening" in the lower parts of the town, when the drink had fairly, or unfairly performed is work, a "shindy" arose amongst the guests owing to a trifling difference of opinion as to whether a certain card which ought to have been in the pack was or was not up a "gentleman's" sleeve and "great ructions" was the result. The "little stranger" was quite forgotten in the uproar, the tables overturned, the furniture broken, and the upshot was that one of the "gentlemen" in question who had well earned a V.C for his vicious conduct on the occasion found himself at the close of the activities in the quiet and reflective atmosphere of the Main Bridewell. On the following morning the culprit was brought before the magistrate, and charged with riotous conduct and wilful damage. In reply to his worship the prosecutor, a dock labourer, who had [true to his Irish nature] forgiven the repentant culprit, said, "I didn't care a button, your honour for all he broke, or for all the things on the chimney piece, only for the two beautiful pictures he smashed to pieces" "And what were they?" said the magistrate. "Well your worship" he answered, "one of them was the Pope, and the other was Tom Sayers, and it was a mudherin pity to break them to smithereens". Poor fellow no doubt, prized these two pictures beyond all he had, the one symbolising his faith, the other his admiration for pluck and endurance. He probably never reflected on the whimsical, association of the gentle tender-hearted. Plus with the lion-hearted hero of a hundred fights, but still he had a veneration for the head of his church, and a hankering regard for the prince of pugilists.

Betting on horse-racing is a practise which has enormously increased in Liverpool and indeed, throughout the country, of late years. To a poor man who lacks that balance of judgement, which would enable him to resist the impulse, the chance of getting six or eight half-crowns by the investment of one is very tempting, although he probably knows that the chance is really nearer 60 or 80 against his winning. The man that bets that a certain horse in a race won't win has an immense advantage over him who bets that he will win, and so the bookmakers thrive on the backers.

Along Victoria Rd, at the extreme north end of Great Howard St, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway runs on a series of arches extending as far as Sandhills. Beneath and around these arches, about noon every working day, may be seen a motley crowd of as villainous an aspect as can well be imagined. Here the smallest of the small fry of bookmakers assemble, between 12 and 1pm to pick up the shillings and half-crowns of the dock and other labourers, who rush in crowds to back favourite horses for the "Grand National" the "City and Suburban", "The Great Lincolnshire" or any other event in the day's programme. The speculating dock labourer is here in great force, especially when any important race is pending, and here American or Irish horses are in great demand from a hazy idea that Hibernian or Yankee owners always "run to win" "Fred Archer's mount" if only on an animated broomstick is always popular, and is well back owing to unlimited confidence in his skill and determination. This is the ragged "Tattersall's" of the north-end, this the charmed spot where may be found the "only and authorised", the "specially appointed" the "private and confidential" agents of the Newmarket training stables, directly connected there by private telephone or secret spiritualism, where the "straight tip" may be had, and the winning horse infallibly spotted for a small sum of two-pence.

This is the rendezvous before the race, the trysting place for "settlements" is in another locality. Back of the Stanley Hospital, almost within earshot of the patients, on a piece of waste brickfield, congregates towards 7pm, another crowd of similar outward aspect to that of the morning, but differently constituted. The "honest" bookmakers turn up to pay their losings and the winners, who from the evening papers have learned their success, converge from all directions on the ground to receive their money. Those who have lost, that is to say five-sixths of the morning congregation, of course are absent from the evening service and find relief at the street corners, or in the public-houses, by curses on their own fates and maledictions on the "infallible" tipsters. And do the nameless and vagabond bookmakers always come to the scratch to pay their losings? In the great majority of cases they do for two reasons, they are financially able to meet their engagements through the generous contributions of the above five-sixths, who have paid their stake and won nothing, and on the grounds that honesty is the best policy, and any default in the matter of settlement would not alone ruin their "professional" character in the future, but subject them at the very first opportunity to the awkward but prompt and inevitable, penalty of "welshing" whenever or wherever they might be caught in public again.

The darker episodes of low life in the betting ring, one man won 50 pound on the last Grand National, went on a 6wk spree, lost his work, then his reason, and finally by his own hands lost his life. How another pledged his watch, his own and his children's clothing, and staked the proceeds on the Chester Cup, losing all and having his house sold up for rent the following week, how petty thefts, all sorts of purloining and embezzlements, begging, borrowing, and stealing, are initiated and encouraged by the ragged regiment of bookmakers, who thrive and vegetate upon the wretched dupes who are drawn within the noxious influence.

The police are well aware of these meetings, that they pass up and down daily and nightly on the outskirts of the crowds, that they never interfere, but it is alleged that so long as the fraternity confine themselves to private ground, they cannot be interfered with. Be this as it may, many a thriving tradesman, many a prosperous mechanic, many a well brought up clerk and shopman has been driven by betting to the docks for a living, and many a dock labourer to ruin and degradation by the same practise.

Drink can hardly be said to be a recreation, but an indulgence, one of which the dock labourer occasionally partakes pretty freely. It is only, however, occasionally, and it may be well understood that a man whose average earnings the year round rarely exceed 18s a week can spend little on drink if he does any kind of justice to himself or his family. The dock labourer's love of the "flowing bowl" is greatly exaggerated, and is not nearly so strong as it was 10 or 15yrs ago. Many causes have contributed to lessen the consumption of beer amongst the labouring classes, mainly the greater spread of education, higher prices of rent and food, and perhaps the prevalence of sounder moral standards in these classes than previously existed, the fact is well known that the public-house business along the line of the docks was never at so low and ebb. There are dozens of these houses where years ago a roaring business was done that barely pay expenses now, in contrast to which the cocoa-rooms are daily full to overflowing. It is quite true that when a man or batch of men have been part of the week carrying sacks of grain, or working two days and a night continuously in a ship's hold they have a substantial sum in wages to draw on the Saturday night, and it is true that they do not always, as the goody-goody temperance people of the strait-laced kind would have them, go direct home and take their wives and children right off to the nearest draper's for an outfit, but being human and not angels they generally go to the neighbouring public-house and have a few pints of ale each, to wash down the week's dust, to have a comfortable smoke and a quiet talk upon matters in general, and their prospects for the next week in particular before shaping for home. This is exactly what the great majority of dock labourers do, and when they reach home they separate the "godly" from the "ungodly" handing the former [the great bulk of their wages} to their wives and retaining the latter [a few shillings] for tobacco, and perhaps a pint or two on Sunday afternoon.

It would be easy, indeed, to find fault with these men on the score of thrift, but it would be just as easy to prove that they, as a body, are not one whit more extravagant in the matter of indulgence than any other body of men, or that they are quite as provident according to their small means, as those of a higher and more pretentious rank. It is too much the role of this latter class to lecture the working man, to pelt him with proverbs, smother him in tracts, and sermonise him to death on his habits. From the language of his betters it might be supposed that the Free Library was built and furnished for his special use, that the Art Gallery was hung with the ancient masters and modern daubers for the sole purpose of developing his taste, and that the new bishopric was created with the single view to his higher moral and religious training. He happily does not accept these boons as a special providence. He has little time to read, and even if he had the circumlocutory processes to be gone through before he could borrow a book from the Free Library first deter and then disgust him, and he cannot afford to walk a mile and a half after his day's toil in his working clothes to sit in the genteel company which patronises the learned precincts of the reading-room. He knows nothing about art, except occasionally the art of self-defence, or the more pressing art of striving to make both ends meet out of his scanty earnings. Nor, if he visited the Art Gallery three times a week for twelve months does he discover [what his aesthetic critics think he ought] any refinement in his tastes by the contemplation of that picture of Sir F. Leighton's which shows a powerful man on his back on a rock, and seemingly painted with a whitewash brush, so coarsely are the colours laid on, costing ever so many hundreds, or that other battle scene, the gift of a popular brewer, costing a thousand, either of which, to an outsider ignorant of the names of the artists, would be dear at so many shillings. To tell the truth the dock labourer is not nearly so artistic as he is artful, and he probably knows better than his "betters" that, however much a Manchester or Birmingham workman may gain by the cultivation of the "beautiful and sublime" in art, in this prosaic port, at all events, it pays far better to be a good grain-busheller or a skilful rice-sampler than to try his hand at perspective or spend his time in admiring "gems" which, if painted anonymously, would be very properly called "daubs"

Turning from her caricaturists to Nature herself, that nature described by Cowper as "but the effect whose cause is God" a Saturday evening or Sunday afternoon's stroll in Stanley Park is a real and not a sham recreation. This is the favourite resort of the teeming population of the north end of the city, a place of fun, fresh air, and freedom of sport, so thoroughly democratic in tone and society as to be especially agreeable to the working man, his wife, and children. Other parks also claim his patronage, though in a lesser degree, owing to their distance from the heart of the city, and perhaps also to a certain or uncertain amount of gentility which seems to attach to them, and which invariably repels the genuine working man, whether it be in a public park or at a penny reading.

The amusements of the dock labourer are few, and his enjoyments far between. If he takes a glass or two of beer occasionally more than is good for him, he is useful to "point a moral" and if [which he rarely does] beats his wife, he "adorns a tale" which is duly unfolded in the police court, and solemnly reproved on the bench, loudly denounced from the pulpit, and promptly embodied in jail statistics, and finally commented upon in the columns of that misleading London newspaper which has so frequently blackened the fame and character of Liverpool, and libelled the habits and manners of its working men. All of which is made hot, and served up sharp upon the working man's head because he is human only and not angelic!

Chapter VI, The Dock Labourer's little ones.

The mortality returns for Liverpool show that nearly a half of the children born in the city die before they reach the age of five. This is a startling fact, but it can be accounted for. Bad drainage, defective dwellings, and overcrowding, together with that chronic poverty which "is always with us" in large cities, are the main causes of the evil. When the Prince of Wales or any other members of the Royal Family visits the mansions of their country friends, the first consideration, after the hunting arrangements are made, is the drainage. Is there any danger of another attack of that dreadful typhoid which, some ten or a dozen years ago, almost paralysed the nation? Are the main sewers and the closets, and the outlets in good order? If so, anxiety is allayed. If not, the visit is deferred or abandoned, and forthwith the "Lancet" comes out learnedly upon malaria, carbonic acid gas and sulphurated hydrogen, declaring that there is not a dozen noble residences in the kingdom whose drainage is safe or satisfactory, at that at the very least a royal commission of medical savans ought to precede every royal visit, just as a pilot engine goes in advance of her Majesty on the occasion of her annual trip to Balmoral.

To do it justice, the Corporation of Liverpool has of late years wrestled, manfully with the legacy of foul drains, pestiferous courts and alleys, and over-populated localities bequeathed them by their predecessors, and have succeeded materially in reducing the death-rate. Still the city stands high on the tables of mortality. Owing for the demand for houses in the neighbourhood of the docks, the labouring population crowds itself into narrow spaces and wretched courts where neither health nor vigour can be maintained. It is no wonder, therefore, that the little ones, born in penury and reared in such abodes, who rarely ever see a green field or blue sky, who romp in no playground but the grimy alley or the street gutter, gradually die away in thousands, leaving only the exceptionally strong and vigorous to survive. And of many of those left the fate is perhaps still worse, the "survival of the fittest" is not always, "the survival of the happiest" From the nature of the dock labourer's employment, always fitful and intermittent, his children are often compelled to do a good deal of shifting for themselves, and, Liverpool, having no factories, where, they might be employed, street peddling is the only resource left them.

Accordingly the city presents a spectacle in the way of juvenile vagabondism unparalleled in any city in the world. News-boys, shoe-blacks, match-sellers, chip-vendors, and a whole army of unattached skirmishers are to be encountered at all hours of the morning, afternoon, and night, in the squares, streets, crossings, byways, courts and alleys of our streets, unwashed, tattered, and uncared for, almost naked in summer and half frozen in winter, their little faces pinched with want and prematurely aged with starvation, abandoned by everybody and sternly ignored by the School Board. Not even the famous beggars of Mullingar, in the days of "Charley O'Malley," could compare with these miserable creatures in raggedness of garb or persistence of entreaty. On this subject the following from the London Globe of the 14th June 1882, will be useful in showing us how, "others see us"

"Liverpool prides itself with just cause on the enterprise and energy which have given her high position among the leading ports of the world. In one matter however, the great city on the Mersey lies open to grave reproach, nowhere in the kingdom are so many miserable children to be seen. A gentleman who has just returned from an extended tour in our colonies and the United States, states in a local journal that never in the whole of his recent wanderings did he see anything to compare with the terrible condition of Liverpool. He goes even further than this. Having a pretty general acquaintance with most continental countries, he avers that the, state of Liverpool in respect of the number of destitute children, or the degree of their destitution has no equal in any place of which he has knowledge. We fear the indictment is only too true, no stranger who finds himself in the streets of the great seaport at night can fail to notice the extraordinary number of semi-nude and apparently half-starved little ones. Indeed the scandal has assumed such dimensions as to have given rise to debate in the City Corporation. Until Liverpool puts itself right with the world in this matter, her marvellous prosperity and wealth will not afford much cause for boasting. Her citizens are proud of their munificence to foreign missions, let them now reserve a portion of their alms for rescue of the children who, roam about in their midst, homeless and Godless."

It is hardly possible to conceive any "mission" nobler, or one more acceptable to Him who suffered little children to come unto Him, than one directed towards the saving of these little ones from a life of peril and temptation, from want and wretchedness, from cold and hardships. It surely would melt the hardest heart to see a poor, bare-footed, almost naked little child of six or seven, tramping about the bystreets at ten at night in the frost and rain, trying to sell a few bundles of firewood, and crying piteously with the cold and hunger, some poor delicate flaxen-haired girl, some bright-eyed intelligent looking boy, cast upon the angry surface of this hard, stony, city life of ours. Who, then will lend a hand? Who will even help any or all of that noble trio of Christian men whose names and deeds in aid of the mitigation of juvenile suffering are a more conspicuous honour to Liverpool than the erection of temples or the building of cathedrals, than arctic discoveries or heathen conversions? Who will, out of the abundance of his worldly wealth, enable a Nugent, or Lester, or a Postance to enlarge the opportunities of saving the out-cast children of our streets from want, shame, and degradation?

Chapter VII, The Dock Labourer's Politics.

Of every hundred dock labourers at this port, about 75 are Irish or of Irish descent, 15 English, 6 Scotch, 3 Welsh, and 1 foreign. They are all politicians, every man of them, except the foreigner, who judiciously adapts his politics to that of the gang with which he happens to be working, so that for about nine months out of the year he is a Home Ruler, the remainder of the period being impartially divided between Liberal and Conservative views. On the occasion of a parliamentary election the dock labourer does not count for much in Liverpool. The constituency is too large, and the question or questions at issue too remote or too vague, to excite that wild enthusiasm which a municipal election evokes. It is only when a retiring city councillor is opposed by an aspiring one, when the former is characterised as a political recreant who commenced life as a marine-store dealer in Sawney Pope St, and finished it as an autocrat in Princes Park, and the latter is described as the working man's friend, the advocate of electoral purity, and the sworn enemy of the tax-gatherer and the jerry-builder, it is then only that political fervour runs high, opinions, and sometimes blows are freely exchanged, and the very walls of the city break out in angry posters of a violent and threatening character. If it be possible, however, to introduce some, "burning question" into the contest, a question relating to the internal affairs of some remote country, say the restoration of a native Parliament to the Cannibal Islanders, the abolition of the coal tax at Bombay during the winter season, or the prolonged hostilities between Holland and the Dutch, some question which must of necessity be fiercely debated by the aldermen and city councillors during the next twelve months, then it is that the dock labourer is on the warpath, committee rooms are taken, committees formed, registers hunted up, speeches made, house-to-house canvassing started, the newspapers deluged with complimentary correspondence, and the very name of Bogus, the "Princes Park" candidate, the Duffer, the "working man's friend", become watchwords by which the respective friends of "slavery" and "liberty" are distinguished throughout the ward.

Strangely when the Duffer gets in he never says a word about the coal-tax, nor the Cannibal Islanders, and his supporters go on paying rent and taxes as usual, and the same would have been the case with Bogus's voters had he been returned. They would not have cared two-pence, had they got their man in, whether he voted for free trade in marine stores, or voted the other way, and as to the constituency itself, or all the contested wards put together, once a man was returned, even after the fiercest struggle, he might speak and vote as he liked, be on every committee he wished, or on none at all, there was no question as to his votes or speeches, until two years and eleven months had elapsed, when he once more on the completion of his term, became public property, and once more got returned upon another burning question. In the meantime he rapidly sank into political oblivion, he was no longer anything more than a ordinary city councillor, rarely seen in his own ward, and useful only now and then, to take the chair at the League Hall at one end of the city or Hope Hall at the other.

Many amusing occurrences took place at these ward elections, at a contest in a certain ward, the popular candidates headquarters were situated a few doors down a bystreet, the opposition camp being just around the corner. An army of canvassers was enlisted on both sides, cabs and spring-carts, coaches and shandries, besides "traps", moral or immoral, were in constant requisition from 9am till 4pm. About 2pm a cart belonging to a well-known luncheon caterer was driven up the bye-street, and seeing the crowd of hungry loungers about the committee-room door, the driver pulled up and asked the "boys" to give him a hand, which they willingly did in taking upstairs half a dozen trays loaded with A1 pies, ham, sandwiches and bottled stout. These the driver quickly deposited on a table, and taking down the empty trays, rapidly drove off. Needless to say that amidst the rapid onslaught forthwith made on the refreshments by the hungry canvassers, the health of the supposed donor, the candidate, was not forgotten and when the last scrap had disappeared and the last bottle was "decanted" they continued their electoral work with renewed vigour. In the meantime the committee and canvassers round the corner began, during the intervals of the battle, to experience a little natural hunger, but were, cheered by the intimation privately whispered round that a luncheon was ordered by their candidate, and was now on its way for their relief. Time slipped on, no luncheon appeared, a messenger was despatched to make inquiries, only to return with the doleful news it had long ago been sent on and "left at the committee-rooms". What committee room? Horror of horrors, had they been regaling the dastardly villain down the street? Had the mercenary pirates been feasting sumptuously upon their pies, and sacrilegiously quaffing their stout? It was downright robbery! a gross outrage", a fragrant breach of the Ballot Act! Here the curtain drops. To make matters worse the hapless army round the corner lost not only their commissariat, but also the battle by a majority of over 900 votes!.

The first School Board election in Liverpool was fought out on sectarian, not political grounds, here the dock labourers had a decided advantage by means of a most ingenious device invented by a clergyman of the town and worked assiduously by other clergymen of the same denomination. Each voter was entitled to 15 votes, which was the number of members of which the board could consist, more than 15 candidates having been proposed, a contest ensued. These 15 votes might all be given to one candidate, or one vote to each, or five each to three, or distributed in any other proportion amongst the whole. According to the plan, the 5 popular candidates A, B, C, D, and E, were selected and their names arranged in alphabetical order. In the neighbourhood of each polling place the voters, male and female, illiterate and otherwise, were assembled and taken to the poll in batches of 5 at a time, each voter being instructed to plump his or her entire 15 votes for one man. No 1 voting for A, No 2 for B, and so on, commencing again with the next batch, and proceeding until the last available vote was polled. The greatest care was impressed upon No 1 to vote for no other candidate but A, upon No 2 to concentrate all his faculties and votes, solely upon B, upon No 3 to bestow her heart's affection upon C, and so with the remainder. The suffrage being household, the constituency docile, an immense voting power was conjured up from the vastly depths of the town, and successfully applied in raising the 5 popular candidates to the very top of the poll. Not one vote was lost, there was no perplexing debate in the mind of the voter as to how he ought to divide or apportion his votes, no scratching his puzzled head over difficult names of similar sound, but a faithful adherence to one magic name, and a meek but resolute walk to the polling booth, "like a sheep to slaughter !".

Chapter VIII, The Dock Labourer's Religion.

The great majority of dock labourers in Liverpool being Irishmen, are, Roman Catholics, and practical Catholics, and to an extent unequalled by any other class, high or low, in the city, are regular churchgoers. Very many of them, no doubt, never go to church or chapel at all, but they are a minority. An Irish dock labourer no matter how much drink he has had on a Saturday night, will try to attend mass on Sunday morning at any risk. The arrangement of the Sunday morning services at the Catholic churches in the city facilitates very much the attendance of the poorer classes, there are no less than five services at St Anthony's Church in Scotland Rd, the first at 7am, the last at 11pm. The earlier services are crowded with hundreds of worshippers whose poverty and consequent want of decent clothes, would deter them from appearing at a later service, in this respect the Roman Catholics have a great advantage over the members of other churches who have only one morning service, and that late in the forenoon. Should the sceptical, doubt the strong, almost in eradicable attachment , which the Irish dock labourer entertains towards his church, he has only to go any Sunday morning to Scotland Rd, and there see the poor people, badly clad, but clean and tidy-looking hurrying to St Anthony's. Should he desire further information of a statistical nature, he need have no hesitation in applying to the worthy rector of the church, who is no less distinguished by his genial, happy manner, than by his literary tastes and accomplishments, and he will there learn something that will astonish him. He will be informed that the same spectacle may be witnessed simultaneously at every one of the 22 Catholic churches in the city, that the spacious church is full at every service, that one of the services at 10am is devoted to children, besides another at 3pm, that every Catholic family and every member of it is personally known to some clergymen at each mission throughout the city, and visited by him regularly, that the priests must live by and in the midst of their people, and, like a kind of ecclesiastical police, be always on the beat ready at an hours notice from their bishop to take up another beat at a distant part of the diocese, that nearly every Catholic church in Liverpool was built by dock and other labourers, if not stone by stone and brick by brick, at all events, penny by penny, and shilling by shilling, and, finally, that not one penny, of endowment or grant, other than a few trifling bequests, has been received to create, sustain, or strengthen, this vast organisation beyond private and voluntary contribution.

After learning all this the reader need no longer be sceptical as to the state of the other Christian churches in the city, notably those of the "established and endowed". A well-known canon, himself the conscientious and hardworking incumbent of one of the poorest districts in the city, labours industriously in the local newspapers to show that the church attendance censuses are, after all, illusory and unreliable, and that the fact that there are only 90 worshippers in a church built to accommodate 300 does not in any degree affect the piety of the church membership of the 210 absentees. If this be so it will strike most people that there has been a lavish outlay of bricks and mortar, and the spiritual care of the 90 must be and expensive affair.

Dock labourers belonging to the Established churches do not, as a rule, attend morning service to any greater extent, owing, to the monopoly of the seats by privileged pew-holders, to the dry, unattractive nature of the services, and to the reading of a manuscript sermon, which might as well be printed and put under the street doors on Saturday night, to be read comfortably at breakfast and avoid the necessity of going to church at all, saving the preacher and the pilgrim much unnecessary trouble. The other churches are fairly attended by the working classes, the voluntary churches being the most popular, indicating the fact that the more "State" the less people, the more endowment the less gospel.

The "newest thing out" however, in churches is the Salvation Army, this is a windfall for the unattached dock labourer whose theology is hazy, and who feels himself an intruder in the ordinary house of worship. Here he is bothered with no dogma, there is no pew rent, no collections, no prying into private and confidential affairs, and if he cannot preach or pray, he can at least shout, which he does to his heart's content, and with the inward conviction that he has at last been set straight on the direct way of salvation.

Should the dock labourer of an especially inquisitive mind wish to be enlightened in the scriptures, or wish to settle any of the great points of controversy which have convulsed Christendom since the days of Arius or Luther, he could not find in England a more convenient spot for the solution, that the city of Liverpool, here he will find learned doctors and erudite divines, who are familiar with biblical literature and who have turned up and set down, analysed and paraphrased every debatable verse in the scriptures over and over again. If after sitting sufficiently long, at the feet of these Gamaliels, the anxious inquirer cannot be brought to believe in purgatory, then it is to be feared that he may "travel farther and fare worse"

Chapter IX, The Dock Labourer and Fenianism

When lately any attempt is made by some obscure or unknown vagabond to burn down or blow up a public building, the outrage is at once set down by police and press to Fenianism. One or both of these conspirators against public peace gets hold of a murder or an outrage [if Irish, all the better] and forthwith the machinery is set agoing, a theory is adopted, others added, speculation takes a thousand shapes, agony is piled on agony, until a simple homicide is magnified into a horrible murder, and the striking of a smoker's fuse against a dead wall, half a mile from a police station, by a man with a "slouched hat" and square-toed boots" is denounced as "another Fenian outrage!" "another attempt to blow up a public building!" The action of the police in such cases is more ludicrous than amusing. When a murder takes place the circumstances rouse public feeling to a more than ordinary degree, when a diamond or bank robbery occurs, or dynamite is surreptitiously found stowed away under the mayor's wine bin, the first thing the police hunt up with the most amazing pertinacity is "a clue", not the perpetrator, but the "clue". In Lefroy's case, the number of clues "taken up" by the London detectives was enormous. Each morning brought tidings of half a dozen new ones, in the end the persons arrested all proved innocent and were discharged without a stain upon their character, until some smart fellow, not a scientific or professional detective, bethought him of arresting the actual culprit and dropping the "clues". Again after the Phoenix Park murders, a whole batch of clues sprang up, and were instantly seized, but soon abandoned, and so it is with all well-contrived outrages, the detectives are outwitted by cleverer men than themselves, and are utterly powerless to "detect" anything, even their own incapacity, unless furnished with the indispensable "information received."

Modern Feniansim is simply another form of the movement of 48 known as Young Irelandism, similar in its object, separation, and differing only in the precise form of force or intimidation by which that object may be attained. Smith O'Brien was a Fenian in his day, but he declared and made open war upon the enemy. James Stephens and his followers made war also upon the enemy, but it was a secret, guerrilla, intermittent war, a war without any immediate result save that of harassing and thwarting the English garrison without challenging it to open fight. Liverpool being "the halfway house" between Ireland and the United States, thousands of the poorest of the emigrants after the famine of 47 unable to proceed further, settled down here, and laid the foundation of an Irish colony which now numbers 150,000 inhabitants, and they were the progenitors of the present race of dock labourers. It is not difficult to conceive that these English born children of exile were taught by their parents the bitter lesson which compulsory exile ever teaches, that, rightly or wrongly, the Government was responsible for the expatriation for the cruelties to which they were exposed, and the sufferings they had undergone in their own country, which poets had been wont to describe as "first flower of the earth, first gem of the sea" In the hearts of these children, now grown up to man's estate, it was easy to plant and propagate the seeds of disaffection against the Government, and at a time when schools were few and the influence of the Catholic clergy extremely limited, owing to supplying the place of those who were cut off in the discharge of their duties during the cholera of 49, it may well be understood how deeply this disaffection took root amongst the people, and how widely it spread until in culminated in the outbreak of 1868

At this period Fenianism was a real power in Liverpool, far more than was then realised or will ever be known, so long as the organisation exists in Ireland and America, it may be expected that this city must continue to a greater extent than any other in England to be the home of some of its most active emissaries. The movement among the dock labourers here was known at its most flourishing period as the "Hibernian Society", and was governed by "centres" and "circles" exactly as the parent society in Ireland. So powerful, indeed, did this association become, that it assumed the functions of a trade union, and was able successfully to dictate to certain employers of labour whom they were to employ and whom to reject. The prompt action of the Liverpool police, who found their "clue" in Corydon the informer, the execution of the "Manchester martyrs" and the determined action of the Government, frightened the leaders of the movement and a general stampede across the Atlantic ensued, followed by a gradual decay of the organisation here, and for all practical purposes, its final extinction.

It is extremely doubtful whether Liverpool at present can boast a single "circle" if so, it must be a very select one, for although hundreds of the Irish dock labourers are as keen as ever in their hatred for British rule and it is their earnest desire to see that rule banished from the land of their fathers, yet it is certain they belong to no organisation of a revolutionary character, nor does any organisation exist except in the imagination of the "active and intelligent" gentlemen of the pavement.

The recent assassinations in Phoenix Park, Dublin, were the theme of sincere and universal condemnation amongst the dock labourers of Liverpool. These men are no more devoid of the instincts of chivalry, in their own rough way, than their fellowmen of higher rank and more polished exterior, and would scorn to approve of a dastardly act, however, "patriotic" the motive or obvious the provocation. The murder of these two gentlemen was looked upon in quite a different light to that of a bad landlord, the sad, gaze upon the newspaper placard containing startling record of the tragedy was entirely different to what would have lighted up the countenance had the announcement been "Glorious news from Tipperary - another landlord shot!"

Chapter X, The Dock Labourer on Strike.

Although a society for purposes of relief in case of illness, and burial at death, exists amongst the stevedores and dock labourers of Liverpool, still only a moiety of the whole belongs to it, and any serious combination having for its object increase of wages, has for the most part been rather spontaneous than a pre-arranged movement. When it is remembered that even in busiest times when steamship companies are working night and day, and many thousands of men are employed at the various docks, there are still thousands who stand outside unable to get employment, anything like effective combination for any purpose, such as is frequently adopted by skilled artisans, would be out of the question in a branch of labour which is so completely overstocked. Yet on many an occasion the dock labourers successfully combined to obtain their demands from their employers, and though during the struggle men from Glasgow and Bristol were imported, the Liverpool men stood loyally together, and laughed good humouredly at the puny attempts of the outsiders to understand, much less to perform their work. The fact is that every port in the kingdom has its own peculiar style of dock work, and strangers are a long time before they can pick up the many little odds and ends of the handicraft indispensable to a good workman. The class of men that one sees at the East and West India and the St Katherine's Docks in London would be of little use in Liverpool. They can hardly be called men, being, for the most part, overgrown boys, or at best broken-down tailors, shopmen, or street peddlers, and are dear at the wages [five-pence an hour] which they get. One gang of Liverpool men would get through as much work in a day as three Cockneys, besides which, the latter must be paid every night, whereas the more provident Liverpool man waits for his wages until Saturday.

As previously stated the wages for Liverpool have for many years back stood for porters at 4s-6d, stevedores and lumpers at 5s per day of 9hrs, and considering the amount of work they get through, the remuneration which their employers receive in the shape of master-porterage and tonnage affords ample margin for this wage without loss or injury to themselves. For example the rate chargeable on a bale of American cotton would be to the importer about two and a half pence, including weighing, piling back if necessary, and loading off upon delivery. It is quite evident even to an outsider, that this rate, amounting to about 21s per 100 bales, pays the master porter well, and to those behind the scenes, who know how to "man a hatch" economically it is no secret that a good cotton ship will pay 20 to 30 per cent, after all demands are cleared off. The same profits do not accrue from the handling of all produce, but when it is understood that the steamship owners themselves are well represented at the Dock Board, and are also master porters and stevedores, that is to say, the licensing body and the licensees, it may be assumed that the rates have been fixed as liberally as possible, so as to ensure that they suffer no loss in that department of their business. Notwithstanding this, a strong attempt was made some years since to reduce the wages of the men 6d per day, and the attempt succeeded but only temporarily, as sound common sense, coupled with pressure of public opinion, and perhaps a spirit of fair play, ultimately prevailed with the shipowners and other employers, and the 6d was restored. The stubbornness of the men in holding out for a paltry sixpence [the price of a couple of pints of beer] was strongly commented upon by the steam-shipping interest at the time, but this feeling is strikingly in contrast with that which actuates themselves on a larger scale and in a much more gigantic sphere. There is such a thing in the Atlantic steamship trade as a "conference" more correctly a "combination", which insists on extracting 6 guineas from every steerage emigrant to the United States or Canada whilst it is a matter patent to any man who ever crossed the Atlantic in an emigrant steamer that 15s per head for food during 10days voyage will more than cover every demand on the ship's cook and the ship's doctor besides add to this 50s per head freight on a description of cargo that loads itself on this side of the Atlantic and discharges itself on the other, without the slightest trouble or inconvenience to the shipowner, and the sum total 3 pounds 5 shillings would amply repay that eminent individual, leaving a wide margin after disbursement of the ship's expenses, interest on floating capital, and payment of dock and other dues for his country mansion, his horses and carriages, his plate, his new conservatories, and his old masters, and a comfortable balance at his banker's besides. But when we add the general cargo and cabin passengers taken out, it will be seen that the members of the "Conference" are remarkably well able to take care of themselves. At the present writing they are themselves on strike against the New York immigration authorities at Castle Garden, who insist upon levying a small capitation tax upon every emigrant landed there. And these are the men who have been for many years in actual combination to extort nearly 100% over and above a profitable rate of passage across the "melancholy ocean" from the wretched Irish peasant, the persecuted Jew, and the starving outcasts of all Europe.

Dock labourers have sometimes had to strike against working on Christmas day and Good Friday when double pay was refused, but many firms always recognise this claim, whilst others do not admit it, and prefer commencing work at midnight on those days. A well-known case in point occurred a few years ago to a firm of steamship owners largely engaged in the season, in the dead-meat trade and the event was celebrated by a poetic dock labourer in the following fashion :-

"It was all on Good Friday the jolly men did meet.

And they ranged themselves in rows on the pavements of the street,

The porters the stevedores, all standing side by side,

While the noble ship was docking by the early morning tide,

But they would not budge an inch, for the owner, nor the boss,

Without the double pay. They did not care a toss.

If the cargo went to ruin, or the beef went into soup.

To life a rope or truck not a man of them would stoop.

So, away they went, rejoicing at the victory they'd gained,

Never caring for the weather - if it snowed of if it rained.

In the parks - across the water - in the churches some were found,

But to Walker's or to Rigby's the most of them were bound.

And when the evening came along it was a funny sight

To see the jolly fellows begging for a half a night!"

Chapter XI, The Dock Labourers and the Police.

With the exception perhaps of the London city force, the Liverpool police are physically the finest body of its kind in England, and it is fair to add that their general conduct and efficiency is praiseworthy. In the ordinary function of preserving the peace in so motley a population as this, and where the facilities for drink are so great, they are very successful, owing no doubt to the fact that they are themselves a cosmopolitan body, made up of English, Irish, Scotch, Welsh and Manx, and by mutual intercourse and social attrition have their angularities rounded off and their sympathies developed. Although the average dock labourer when drunk is both obstinate and provoking, except he be actually riotous and unmanageable, his meeting with a policeman is generally the best thing that can happen to him. Contrary to what might be expected, locking the man up is the last resort of the officer, and is only adopted when every means of coaxing, advising, and threatening fails. To be sure, violent and brutal policemen sometimes break open a drunken man's head with the truncheon, or twist his arms almost out of their sockets, but the general majority of the force act otherwise and prefer to deal with an inebriate rather as an erring friend than a determined foe. Accordingly the police are a popular body, and along the lines of the docks are always on a friendly footing with the labourers knowing many of them by name, and, when off duty, having, an occasional drink with the most respectable of them. And this is prudent. For in the ups and downs of police life, where "outrageous fortune" is notably fickle, there is no telling when the luckless officer may himself have to leave the force and turn dock labourer, in which case he will find his position far less irksome and his duties more agreeable by his reputation of having been a "good bobby."

Occasionally, a dock labourer from the Emerald Isle may become obstreperous, he refuses to go home and wants to fight all and sundry, when suddenly, a policeman's apparition breaks upon his view, and rapidly dissipates any little prudence the drink might have left him. His natural hostility to anything in the shape of a policeman [he has only just "come over"] at once manifests itself, he makes a fierce lunge for the officer, who dexterously avoids it, and comes down with a crash in the gutter. In response to a whistle, two other officers quickly appear in the twinkling of an eye, the prostrate warrior is at once laid hold of, in spite of his kicking and plunging, and carried off face down to the nearest station or if very helpless taken on a handcart or barrow. Here he is booked as drunk and "righteous", and unceremoniously bundled into a cell, there to rave and curse and kick until his throat and limbs become exhausted, and he finally drops off into a laboured sleep on a wooden bench, from which he awakes next morning, to his own astonishment, to find himself in durance vile. During the process of arrest and conveyance to the bridewell the bystanders never interfere so long as no cruelty or unnecessary violence is practised by the police, the proceedings regarded by his assembled fellow-labourers as if the man were merely being put comfortably to bed, general sympathy, however, being felt for the poor fellow's condition, and an earnest wish on the part of some that they had only half his ailment.

Lowly and sadly they muttered their grief,

As they trundled him off on a barrow,

And silently thought of the headache he'd have,

And the sentence he'd get on the morrow.

Considering the valuable nature of the cargo which must of necessity be freely handled by dock labourers, and the costly packages and parcels which are daily landed from vessels in the docks, cases of theft and pilfering are extremely rare. True, the policeman at the gate and the Customs officer keep a sharp look out, and it is amusing sometimes to see how closely the officers will examine a donkey cart with a bag of wheat or of cotton pickings, whilst a whole load may pass through without question. The theory is, of course, that a single sack of wheat might possibly be stolen, but, to steal 50 would be an act the audacity of which would be incredible. Most of the steamship owners pay for the special services of a policeman, whose duty it is to keep a sharp look-out upon the various packages of produce lying on the quay, and those in the fruit and provision trade also keep watchmen for the same purpose, but as a rule, pilferers when caught, turn out not to be dock labourers, but dock loafers, who never worked a day in their lives except what they were compelled to do in prison. On the whole the labourers at the docks are honest and trustworthy, they have many opportunities to be otherwise if so disposed, in spite of police and watchmen, the fact is fewer dock labourers are arrested for theft in proportion to their numbers, than any other class of unskilled labourers in the city. The only occasions were they make acquaintance with the magistrate are those who follow a drinking bout or a conflict with the police, which is rarely, and considering the precarious nature of their employment, the absence of home comforts and the frequent want of many necessities, the strong temptations to which they are subjected, the dock labourers of Liverpool will compare favourably in moral conduct and honest living with their fellows in any seaport in the world.

Chapter XII, The Dock Labourer in sickness

Sickness and accident are common incidents in the life of a dock labourer, and are frequently anticipated by joining a sick club, tontine, or burial society. A dock labourer's benefit society exists here, from which, by a small weekly payment, members are entitled to a certain amount in sickness and a small sum at death, but the number on the role is few in proportion to the great body of labourers. This is partly accounted for by the difficulty of taking up the weekly subscriptions from such a large body of men, scattered up and down a line of docks extending nearly 6 miles, although the secretary himself a dock labourer, and a man of marked ability and integrity, does his utmost to overcome this difficulty by endeavouring to be in as many places as he can at the same time. Many men, however, join tontine societies up town, and by a payment of 6d a week, secure to themselves 10s per week in sickness, and 10 pounds to their relatives at death, the surplus funds being divided annually at Christmas, and very acceptable at that festive season. But the great majority of dock labourers are unhappily in a position of absolute helplessness, when sickness or accident overtakes them, there is then nothing for it but the hospital or the infirmary, if the illness be prolonged, and, if only temporary, the charity of their neighbours or the kind offices of the clergy. Latterly, the public hospitals at the north end have had their resources taxed to the utmost with cases of accident arising at the docks, in consequence of the migration of the large steamship companies to that end, and these institutions have strong and urgent claims upon the charitable in consequence. Although the subscriptions of the dock labourers themselves to the Hospital Saturday fund, as published in the newspapers, appears small, it must be remembered that the collection is made up at the very worst season of the year, so far as they are concerned, that could be selected, being just when the busy season ends and before trade again becomes brisk. Also it must be borne in mind that large numbers of these men attend church or chapel on Sunday, and subscribe their mites to the Sunday collection in addition to that which they give at the Saturday's pay-table. In fact they give much more in proportion to their earnings than many of the better paid artisans, and if by implication the Hospital Saturday movement was instituted to catch those who never go to church, if honestly responded to, there is no doubt it would make a great haul on the Exchange-flags.

A very high authority on hospitals, a distinguished neighbour of ours, familiar with the subject, strongly advocates systematic instead of spasmodic support for public hospitals, and advises small weekly contributions on the part of the workmen in preference to comparatively large annual donations. This is an excellent suggestion if practicable, but it would be difficult to carry out in the case of dock labourers. These men own no particular master, and are attached to no particular pay table, they may be at MacIver's this week, the White Star the next, and at the National the week after, and although it would be easy to convince them that however and wherever their weekly pennies were dropped they would be sure, ultimately to reach the hospital fund, yet it would be impossible to create and foster in their minds that interest in a particular box and pride in its being respectably filled which operate upon workmen who are constantly attached to a workshop, warehouse, or manufactory.

In his various spheres of work, the dock labourer's life is often a bad one. His frequent exposure to all weathers night and day, sometimes working on the river, bushelling grain in a ship's hold at high temperature, or coalheaving up its steep sides, brings on a variety of bronchial and pulmonary diseases, from a simple cold to aggravated consumption, in addition to which, his life, if a stevedore, is never safe for five minutes, the breaking of a sling, the fall of a cask, or of a bale of cotton, may shatter his poor limbs to pieces or knock the life clean out of him in a moment. As to the Employer's Liability Act it seems to have been framed specially in the interest of lawyers and to the ruin of poor clients. The verdict in every case is almost invariably "for the defendants" so that unless a poor man at the docks is able to fix beyond cavil the responsibility of some petty "boss" or foreman, and disprove also the smallest contributory neglect on his own part, he is simply throwing away what little money his friends may have scraped together to enable him to fight the hopeless battle of "labour against capital" in which the weak always go to the wall.

The sickness, as well as every other calamity, the poor is the never-ending friend of the poor. So far as their little abilities allow them, a sick labourer is never forgotten by his "mates" and even the neighbours poor as himself drop in occasionally by his bedside to cheer him up, to give him the latest news from the docks, and often bring him some little nourishment or delicacy which may alleviate his condition. His fellow-labourers very frequently, in case of prolonged illness, get up a subscription at the pay-table on a Saturday evening on his behalf, one or two of the "bosses" lending the weight of their presence at the proceedings, and sums amounting occasionally to 2 and even 3 pounds, are made up, which two trusty friends of the sick man take to his house and hand over to his poor wife, whose joy knows no bounds when she finds herself able to get her ailing husband some long desired dainty for his palate or nourishment for his wasted frame. And the eager expectancy, the grateful looks which sparkle from the eyes of the poor children when these true Samaritans come to relieve the stricken household tell plainly enough the sad lesson that when the breadwinner is laid low his little ones suffer, that want and privation, cold and hardship, are the lot of those who sit around that cheerless fireside.

Chapter XIII, The Dock Labourer's End

"Deceased was working in the hold of a vessel at the docks, and when in the act of hooking on a bale of cotton, another bale which was being hoisted at the time, slipped from the hooks and fell upon him. He was immediately taken to hospital, where he died shortly after admission. Verdict, "Accidental death."

Such is the record one meets with almost daily in the newspapers, and it is the final chapter of a life of - perhaps much improvidence and sad shortcomings, but also of hard labour and great privation. The unfortunate man has been working at the docks, off and on for 30 yrs or more, but his fate has overtaken him at last, and he dies in harness - not a very glorious death indeed, such as is sung by laureates or chronicled by historians, but yet a death which terminates a useful life and may teach a useful lesson.