Leicester Chronicle, April 7th 1866

Marriage

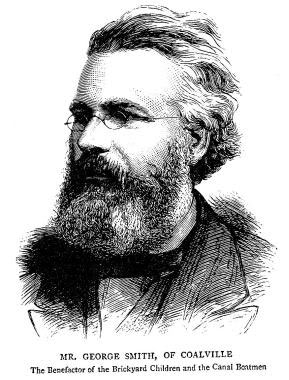

On the 19th ult at the Parish Church, Ockbrook, Derbyshire, Mr George SMITH, of Coalville, manager of the Whitwick Colliery Companies, Tileries, to Mary Anne, 3rd daughter of the late George LEHMAN, of the above place

Leicester Chronicle, Oct 19th 1867

Mrs George SMITH, of Coalville, laid the foundation stone of the new Primitive Methodist Chapel, Ibstock, Oct 14thg 1867, was presented with a handsome silver trowel

Leicester Chronicle, May 30th, 1868

Mr George SMITH, of Coalville, Monday last elected member of the Leicestershire Architectural and Archaeological Society

Leicester Chronicle, Dec 4th, 1869

We have received the following letter from Mr George SMITH, of Coalville, which tells his own sad story. May we hope that during the forthcoming session of Parliament the condition of the poor children in brickyards will have consideration.

Where is the Clarkdon or Wilberforce of the present day who will plead the cause of the poor "little ones" who are suffering ?

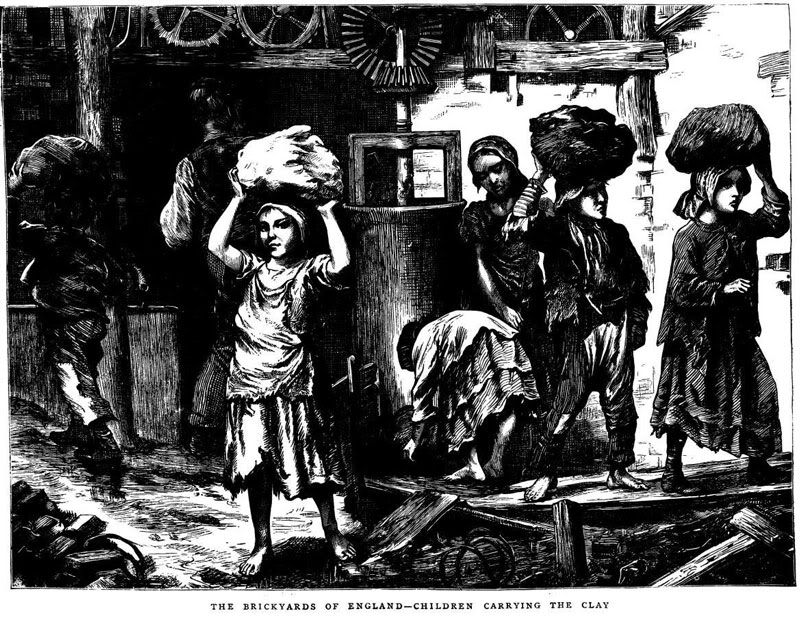

The following facts illustrate the deplorable condition of the brickyard workers in Leicestershire and Derbyshire in 1869. Some of the boys employed are about 8yrs old, each one is engaged in carrying 40-45lbs weight of clay on his head to the maker for 13 hrs a day, transversing 14 miles. The girls employed are between 9 and 10 yrs of age. They are not engaged in carrying clay on their head the whole of the day but are partly occupied in taking bricks to the kiln. Some of the children are in an almost nude state. Many of them in Derbyshire work what is called "eight hour shifts" which reckoning from 12pm on Sunday to 12pm on Saturday night following, make a weekly labour of 75 hours. To ascertain really what work these children have to do, we must suppose a brickmaker [not over quick in his operations] making 3,500 bricks per day. The distance the child has to travel with mould, weighing four and a half pounds with bricks in it ten and a half pounds, one way, and back to the brickmaker with mould only, is upon average 12 yds. This multiplied by 3,500 makes the distance nearly 24 miles, that each child has to walk every day, carrying this weight with it.

I assert [says Mr SMITH] without fear of contradiction, from 30yrs general observation and practical experience, that masters are not gainers by employing children of such tender ages, and for so many hours. I feel strongly that girls should not be employed in brick and tile yards on any account, as the work is totally unfit for them. To see the girls engaged in such work, and at such unseasonable hours, mixed up with boys of the roughest class, must convey to the mind some idea of the sort of wives, with such training, they will make, and the kind of influence they will eventually bring to bear on society.

In agricultural gangs, printers, bookbinders, factory hands, iron and tin workers, potters, brick and tile makers, who employ 50 hands or upwards, and numerous other trades where the work is not nearly so laborious, have the hours of labour restricted why should not all yards, irrespective of the number employed ? What I contend for is, that if the Factory Act is good for 50, it must be good for 20 or less.

If it was more generally known what amount of ignorance, vice, and immorality, prevails in brickyards, we should not wonder at so very few of the girls employed making good house-wives, or at the boys finding their way into the jails, or becoming inmates of the workhouse, instead of growing up respectable members of society. Mr MUNDELLA said the truth when he stated in the House of Commons that " ignorance, vice, and immorality prevail to a greater extent amongst the employees in brickyards than in any other trades" In all probability this will remain so, unless something be done by the Government to counteract it. Certainly, I think that the time is come when the children employed in our brickyards should have extended towards them a helping hand, so that they may be elevated religiously, morally, socially, and intellectually.

George SMITH, Coalville

The Pall Mall Gazette, Jan 7th, 1871

Mr George SMITH, of Coalville, having written to the Home Office to ask whether the Government intend during the next session to take into consideration the condition of brickyard children as related to the Factory and Workshop Acts, has received a reply from Mr BRUCE that the subject will be considered in the next amendments of the Factory and Workshop Acts, but it is doubtful whether a bill for that purpose can be introduced during the next session

Liverpool Mercury, May 1st, 1871

Publications, Speedily will be published

"The cry of the children, from the brickyards

A statement of facts and an appeal with remedy

Mr George SMITH, of Coalville

The Graphic, May 27th 1871

Brickyard Children

The question of child labour, and the extent to which it may be legitimately employed, has, especially of late years, frequently engaged the attention of Parliament. The publication of "Michael Armstrong" and now forgotten novels of the late Mrs TROLLOPE, produced besides their ill-concealed political bias, no little stir at the time, and materially assisted in awakening the active sympathies of the public on behalf of the myriads of little ones doomed, from very infancy, to a life of cheerless toil, when they should have been at school or in the playground. So painfully impressed was Mrs Browning with the sickening disclosures made concerning the oppressive manner in which the factory children were often employed, that she threw all her energies into her well-known "Cry of the Children" a lyric which speedily acquired a popularity second to that employed by Hood's "Song of the Shirt" Ultimately, the demand for legislative interference became so loud and unanimous that Parliament was compelled to pass the measures popularly known as the Factory Acts, notwithstanding the powerful opposition of the principal employers, who denounced these acts as a serious violation of the fundamental principles of political economy, an opinion certainly not shared by the leading political economists. At first the Factories Act did not produce the results anticipated, and it was feared they would prove a failure, but the introduction of what is called the half-time system, whereby the children of a certain age are allowed to work three days per week in the factory, on condition that the other three days are spent at school, has unquestionably assisted in bringing about a satisfactory solution of the difficulty, and the great industrial establishments of the north are now almost freed from the reproach under which they had long laboured.

But child-labour continued to be employed in numerous industries not reached by the Factory Acts. Thousands of children were found working in coal and other mines in various parts of the kingdom. Here again the law after some delay, stepped in to the rescue of the helpless little ones. But the need for legislative interference was not yet at an end. The startling revelations made in connection with the agricultural-gang system showed that child slavery existed in the country as it did in the town. It was but the other day that the legislature came to help the little rustics, and already we hear of fresh appeals on behalf of the children of further painful disclosures which almost prompt us to ask whether our boasted civilisation be not a cruel myth. It has been shown on indisputable evidence, that at the present moment there are in our various brick-works, between 20,000 and 30,000 children, from the ages 3 and 4 up to 16, undergoing what has been expressively described as "a very bondage of toil and horror of evil-training that carries peril in it" Mr George SMITH of Coalville, near Leicester, who has for several years past devoted himself to the work of making public the condition of these children and young persons, and who has just published a descriptive pamphlet, full of terribly interesting details, tells us that as a child and lad, he has himself gone through what thousands of children are going through at the present moment, that he has himself borne and been borne down by the oppressive "burdens" that young backs are still bearing, has himself breathed the polluting moral atmosphere still breathed by the miserable child-workers, and that he is marked by indelible scars, the silent but eloquent witnesses of the life of pain and suffering from which, unlike the mass of his fellow workers, he has happily contrived to escape. Such a man is a fit champion of the poor little ones whose cause he has courageously exposed, and to his earnest pleadings it is impossible to turn a deaf ear.

Some idea in which the brickyard children are employed, more particularly in the midland counties, children of both sexes are engaged in carrying lumps of tempered or "pugged" clay, used in making bricks to the brickmakers. The children are usually very thinly clad, sometimes almost naked, their hair being matted with wet clay, and at the end of their day's labour they appear completely exhausted.

At the Social Science Congress last year, Mr SMITH exhibited a lump of solid clay, weighing 43lbs, this, in a wet state had been taken three days previously from off the head of a child aged 9yrs, who daily had to walk a distance of twelve and a half miles, half that distance being traversed while carrying this heavy burden. The calculation was thus made, the brickmaker manufactures on average 3,000 bricks per day, these weigh sometimes 12 tons, the whole of which has to be carried by two children from the clay heap to the brickmakers table. The distance between the heap and the table is about 35yds, and the number of journeys to be made by each child to and from the clay heap, amounts, as above stated, to twelve and a half miles. The employment lasts 13 hours per day, sometimes longer, except during the slack season. If the children are not sufficiently quick in their movements they are punished with curses and blows from their task-masters. Mr Robert BAKER, in one of his official reports, says he has seen a boy 5 yrs old being "broken in" as it is termed to the labour. "In one case a boy of 11yrs of age was carrying 14lbs weight of clay upon his head, and as much more within his arms, from the temperer to the brickmaker, walking 8 miles per day upon the average of 6 days." This is painful, but still more so is the following statement, also by Mr BAKER :- "I have seen females of all ages, 19 or 20 together [some of them mothers of families], undistinguishable from men, save by the occasional peeping out of an ear-ring, sparsely clad, up to the bare knees in clay splashes, and evidently without the vestige of human delicacy, thus employed." that is, in carrying the moulded bricks. These women, so lost to all sense of shame, so unwomanly in appearance and habits, were, be it remembered, simply the grown-up child-workers. What other result would be expected from such a beginning ? But we must refer to the painful subject again.

The Star, July 18th 1871

The horrors of the Brickfield

Lord Shaftesbury had so clear and terrible a case for the children employed in the brickfields that it is only possible to wonder why Parliament has not interfere on their behalf before. Mr MUNDELLA has brought a Bill into the Commons, the main provision of which Lord Morley has promised to incorporate in his Bill which is now before the House of Lords. Mr MUNDELLA, however must have the credit for the legislative initiative. The honour of calling attention to these children belongs to Mr George SMITH of Coalville, near, Leicester, who for many years has been pointing out the horrible oppression which is going on unremedied in our midst. He was once a sufferer by it, and has nobly devoted his time and energy to rescue the present generation of children from it. Here are we, English people, every ready for any work of philanthropy, stretching out a strong arm to rescue the African and Polynesian from the man stealer, and all the while there are little boys and girls living in worse than African slavery in the brickfields round all our growing cities. One fact tells the terrible story of thousands. "I had a child weighed recently" says Mr SMITH, he weighed fifty two and a half pounds he was employed in carrying 43lbs weight of clay on his head an average distance of 15miles daily and worked 73 hrs per week. Lord Shaftesbury has still worse to tell the House of Lords in his speech on Tuesday. Nor are these little-clay carrying slaves few and far between, there are 30,000 young persons employed in the brickfields, whose ages range from 3 to 17 years. The condition of raggedness, dirt, ignorance, and immorality in which a large part of these boys and girls exist may be imagined. Lord Shaftesbury and Mr MUNDELLA have done service in calling attention to their condition and in asking that they should no longer be kept out of the pale of law. What claim the brickyards ever had for exemption from the Act, which protects women and children, it is hard to understand, the claim now is for even more rigid application of the law to the exceptional needs and sufferings of these little English slaves. - Daily News.

Morning Post, Sept 8th 1871

A cry from the Brickyards

Mr George SMITH of Coalville, Leicester, has issued an urgent appeal on behalf of the poor children, employed in the brickyards

"Ones eyes inevitably gather in a mist of tears over that old, old story of the brick toilers in Egypt in the dear old Book, pathetic bits of which you have prefixed. I have no fault to find with preachers at this late day, be they in church or chapel, fetching thence text for "doctrine, reproof, correction, instruction and righteousness" The "hard bondage" of these far back brick makers and their deliverance by Him who "hears" and "remembers" are imperishably worked into the mightier story of a mightier Redemption, and thence through all succeeding ages men shall turn and return to the divinely-simple record. But after all it is an old story, and all the sufferers in it long at rest. So that sooth to say o' times, I yearn for less preaching about the dead past, and more sympathetic practise in the living present, aye, within the very range of the old-world tragedy of these brick makers. For there are in this our own England brick-toilers and "hard bondage" in brick making, that are sending God-ward "sighs" and "groanings" and "cries" of the most tragically sorrowful sort - "sighs" and "groanings" and "cries" from the midst of ourselves in this so vaunted 19th century, that might well bring down our preachers - and others to - from their pulpit dignities and properties, and impel them forth - like unto Moses - to "look" on the "burdens" and catch up the cry of the presently wronged and helpless. May my poor words take a grip of some few hearts and consciences!

"It is told of a sailor returned from a far voyage, after many chequered years, that landing in one of our great seaports, and chancing to find himself in a back lane, he there saw a cage of birds suspended at a shop door, he took out one, and another, and another of the captive birds, and softly tossed them up into the free air, following their flight with beaming face, and that then he stood, with purse in hand, ready to pay the price of all. The money having been paid, and the sailor being wonderingly questioned on his singular conduct, he with wet eyes recounted his own experiences, ending with these words, "I have myself been a prisoner and know what it is to pine for liberty, and I wouldn't have the poor birds kept there."

"Similarly in this thing of the brick toilers and their hard bondage, and the cry of the children that I want to make articulate and penetrative, to the many loving hearts of my fellow countrymen and countrywomen I write not at all from the outside or as a mere spectator. As a child and lad I have myself gone through what thousands and thousands of boys and girls are today going through, have myself been borne and been borne down by the "burdens" that young backs are bearing, have myself breathed the polluting moral [that is immoral] atmosphere they are breathing, carry myself scars that must go with me to the grave, through hurt and wrong they are still enduring. Accordingly, the basis of my statements, as the impulse to my appeal, rests on an actual, personal experience of the ongoings in England's brick-fields and brickyards, while since I became a man I have been and still am in constant relationship with the trade. My heart is sore for the "little ones" and stirred with indignation against the unwomanly and unwomanising .work assigned to these mothers and sisters, and I must speak out. All honour unto reverence to Mrs Barrett BROWNING for her passionate as compassionate lay of the "Cry of the Children" scalding tears have baptised it with holier chrysm than apostolical hands, but my humble utterances must be in hard prose, with scarce a gleam of poetry illumining. I make no pretence to author craft or fine sentence writing. I aim at telling simply a dark chapter in the "annals of the poor" Throughout I speak that I do know. "The matter of fact that I should wish to bulk out in all its largeness and shame before the philanthropy and Christianity of England is, that in our brick-fields and brick-works there are from 20,000 to 30,000 children from as low as 3 and 4 up to 16 and 17 under going a very "bondage" of toil and horror of evil training that carries peril in it. Then "I claim the protection of the law for these children specially, and all children universally, by placing them within the inspection and regulation of an act kindred with the Workshops or the Factory Acts.

"These are the two main things that I seek to make good to every candid reader and inquirer, and as against those employers and enforcers of child labour, who mistakenly regard it as their interest to maintain the present system [or no system] So far as I know my own heart I am anxious to exclude personalities, to avoid giving pain to individuals, but it isn't easy, perhaps impossible, to expose wrongs without hitting the wrong-doers, to place before the community actual facts, and not lay oneself open to accusations of personal animus, and all the rest of it. Throughout my endeavour shall be so to put the case of my little clients [if I may be allowed the honour to call them so] as to prove a wrong and secure a remedy, shrinking from no obloquy or misconstruction, because of telling "the truth the whole truth and nothing but the truth".

Locally, I have from time to time, through a goodly number of years, met the objections of given employers and their mouthpieces, even when the delirious violence of their language placed them beyond the pale of recognition within civilised society. But as it is ill contending with a chimney-sweep without being blackened, or a baker without being whitened [each alike unpleasant], or unmetaphorically, as it is only to involve one in unvailing argument with ignorance and imagined self-interest combined, to try to convince certain underbred, if wealthy, masters of brickyards and their lackeys, I shall prefer putting my data with all integrity and carefulness before the public, and leave them to make their own way, i.e., disentangled from merely personal charge and countercharge. I the more readily carry out this design from the abounding proofs received, that many employers are really unaware [culpably unaware] of the ongoings in their own brickyards. "I have then to show first, that in our brick-fields and brick-yards there are from 20,000 to 30,000 children from as low as 3 and 4 up to 16 and 17, undergoing a "bondage" of toil and a horror of evil training that carries peril in it."

The remedy Mr SMITH proposes is as follows :-

"1, I seek absolutely to prohibit infant and child labour in brickyards [as everywhere] such as has been superabundantly proved to exist extensively, whereby, the merest dots of "little ones" from three to four to seven and eight upwards are "broken in" and kept to labour.

"2, I seek absolutely to prohibit the employment of girls and women in the work of brickyards

"3, I seek to have it enacted that no one shall be permitted to work in brickyards sooner than the twelfth birthday, and then only when certified to be able to read, write and cipher.

"4, I seek to lessen the hours of labour to a maximum of from 8 to 10 hours, and from 12 to 14 years or thereby to permit only alternative days working the latter preferable to half-time, which has practical though not insurmountable difficulties.

"5, I seek to have official supervision of the health and treatment of all juveniles in brickyards, and punishment to be felt by breakers of the law.

"6, I seek to place all brickyards, tileries, and the like under an amalgamation of the Factories Act and the Workshop Act, including all employing under as well as over 50 hands.

"7, I seek to have inspectors and sub-inspectors who know the usage of the brickyards etc, and the inspection to be universal. At present not more than 100 brickyards out of 2,825 are thus inspected."

The Morning Post, March 18th, 1873

The Brickyard Children

The Earl of Shaftsbury will present a valuable testimonial, in recognition of his services, to Mr George SMITH, of Coalville at a meeting to be convened for that purpose in the Social Science Rooms in a few days. Lord John MANNERS, Mr MUNDELLA. M.P, and other well-known public men will take part in the proceedings

The Graphic, May 21st 1879

George SMITH of Coalville

This well known philanthropist to whom the brickfield and canal boat children owe a deep debt of gratitude was born in Clayhills, Tunstall, Staffordshire in 1831. His father was a brick and tile maker and George himself, after attending school for some time, was set to work at the age of seven to earn his own livelihood by carrying the clay and bricks to and from the makers to the drying floors and kilns. When only nine years old he had to carry forty pounds of clay for thirteen hours daily, and besides this to sit up all night twice a week to watch the ovens. Yet in spite of these long hours of heavy labour for a child of such tender years he managed to work overtime, and devoted the whole of his extra earnings [one shilling per week] to the purchase of books and paying for the admission to a night school. The education thus obtained, but by no means brilliant, was sufficient to enable him after years to set forth in fervent emphatic language the wrongs and sufferings of the poor brickyard children, among whom he himself had laboured. For two long years he advocated their cause, keeping the subject constantly before the public mind by persistent letter writing to various periodicals, by speeches at public meetings, and by repeated applications to Parliament and the Home Office. His determined and patient efforts at last met their reward, when in January 1872, 10,000 brickyard children were taken from their slavery and sent to the schools.

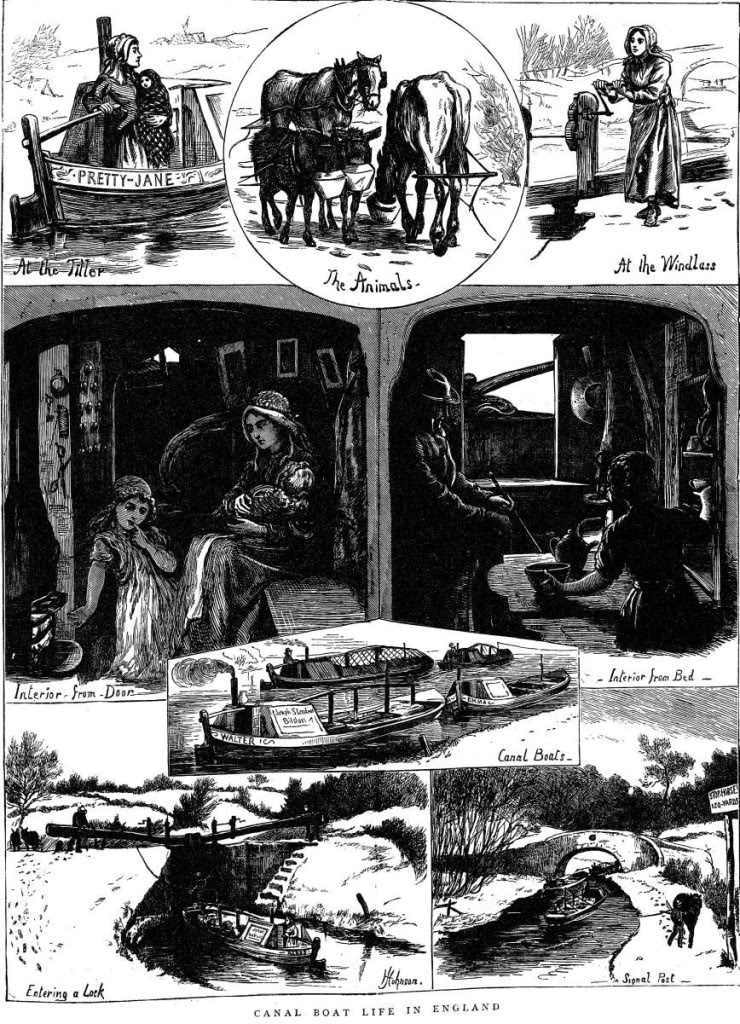

The achievement of this victory gave him new courage, and it was not long before he was again in the field, fighting for the miserable and helpless children of the Canal Boatmen, "Floating Gipsies" as he called them. Again he pleaded with rough untutored eloquence, describing with faithful portraiture the insanitary and often immoral conditions in which these people lived, and again his earnest patient zeal was rewarded with success by the passing of the Canal Boat Act in July 1877. With the modesty which ever accompanies true worth George SMITH has never claimed any credit for these great works and has scarcely ever alluded to the expense which he incurred although he has been a poor man all his life. He has spent more than £2000 out of his own pocket, and sacrificed an appointment worth £450 a year in order that he might devote his life entirely to the work. The only substantial public acknowledgement of his labours has been the presentation of a testimonial consisting of 100 guineas and a piece of plate, and now we hear that he and his family are in positive distress. This being the case an influential Committee of which Lord Aberdare id chairman, has been publicly appointed to collect subscriptions for a testimonial fund, and it is confidently hoped that the sum collected will be such as to place Mr SMITH beyond the reach of want for the remainder of his life.

Donations may be sent to Messers BARCLAY, BEVAN, and Co's, Lombard St, or to the Hon secretary of the "George Smith Fund", Mr P. W. CLAYDEN, 13 Tavistock Square, W.C.

The Graphic, March 13th 1880

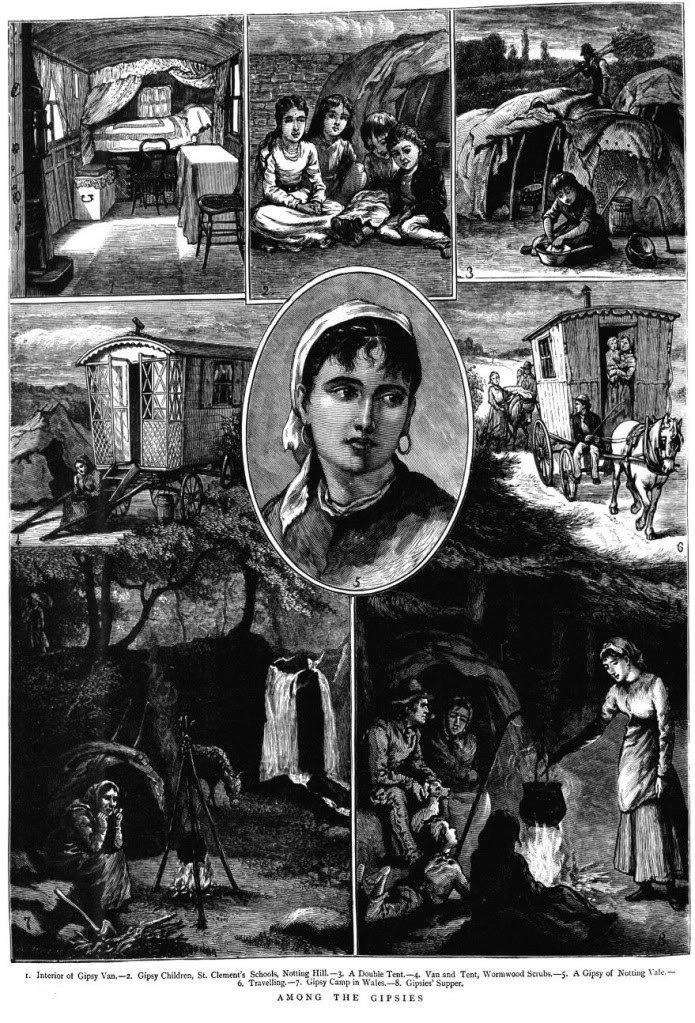

Among the Gipsies

For many centuries, perhaps, no class of people have been the subject of so much keen prying curiosity as the gipsies. More than 150 authors have dealt with them in one form or another, and a variety of names have been given to them, one of the most earliest was Lury. The importance of Lury is spoken of by no less than five Arab writers, first about 940 by Hamza an Arab historian, next by Firdusi in 1126, in the 15th century by Mirkhead, the historian of Sassanides. They are also called Lyntas or Djatts, the name of one of the tribes of the ancient Indian races still widely diffused throughout the Punjab. There are a number of other low-caste tribes in India of which our gipsies are the outcome, and these are the Changars, the Sanseeas, Sinders, the Natias or Nuts. The characteristic features of these tribes correspond exactly with our gipsies previous to mixing with the Gorgio or Gentile - viz, living in tents covered with old rags and blankets, their low filthy habits, idleness, robbing and plundering all they come in contact with during their wanderings, the reason for the gipsies emigrating from India may be set down to their roving habits, love of plunder, dislike to war, and the famines that sweep over India periodically. Prior to their emigration fearful and terrible wars, on account of the Mohammedan faith, ravaged all India for several centuries, during the 10th and 11th centuries under Mahmood the Demon, at the end of the 14th and commencement of the 15th centuries under Timur, who butchered in cold blood over 500,000 Indians. The gipsies travelled through Persia and by the Euphrates Valley route in large numbers and arrived before Constantinople at the end of the 14th and early in the 15th centuries. The main portion, then something like 200,000, settled in Wallachia, and from thence, and about this time, they began to people Europe, travelling in large parties of several hundreds, and in some cases thousands. They arrived in Scotland about 1514, and from that time have permeated their way into every hamlet, village, town and city in this country.

It is generally supposed, and there are good grounds for the supposition, that there are between 700,000 and 800,000 gipsies in Europe. In Roumania there are 250,000, in Servia there were in 1874, 24,691, in Hungary 159,000, in Transylvania 78,921, in Spain 40,000, in Russia 48,247, in France 6,000. In the days of Hoyland there were between 15,000 and 18,000 in this country, and, judging from the calculation I have made there must be fully this number of gipsies in England at the present time, and owing to the addition of our native wastrels, these wandering tribes are on the increase. There must be close upon 2,000 living on the outskirts of London.

Some of the gipsies, called house-dwelling gipsies, live in our back slums, about four fifths of our gipsies are living in tents or vans, and move about the country at different seasons of the year. A gipsies tent is composed of some long sticks bent, and over which are thrown some old blankets, sheets, rugs, and old sacks, according to the wealth of the gipsy owner, these are fastened upon the sticks with skewers. In the centre of the covering is a large opening, through which the smoke from their fire of wood or coke, as the case may be, passes. Inside the tent an old tin or iron bucket serves as a cooking range. The bed consists of a layer of straw upon the damp ground, which has to be replaced every 10 to 14 days with new straw, or it will either become rotten or broken to dust. A gipsy woman told me a few days since that she had seen their straw beds "so rotten that they could be pulled like strings". The gipsies generally pitch their tents and form their encampments in swamps and low marshy places. Their tent furniture, cooking utensils, etc, consist of an old chair, a few boxes, a large saucepan, and one or two dishes. Their bedding and clothing in many instances consist of old rags. Some of the better class gipsies will have bed linen and changes of wearing apparel. Washing either themselves or their clothes is a luxury they seldom indulge in. A gipsy woman told me a month ago that she "only washed once a fortnight, and then she caught cold after it." I have seen gipsy children who have not been washed for years. In some instances the children have presented a kind of piebald appearance, which as either been caused through perspiration or the dirt peeling off their faces.

Not much regard is paid to the separation of the sexes in either the tents or vans. In the case of grown up children, sleeping in the caravan as father and mother, they generally sleep under the parents bed at one end of the van. To pack father, mother, and eight sons and daughters of all ages and sizes in either a tent or van to sleep must be a process similar to packing herrings in a box, and as I have seen them coming out of their tents I have been puzzled to know how they would have lain. Fully two thirds of the gipsies living together as man and wife are unmarried, most of those who have been married have been "tied together" by the clergyman gratuitously.

The present race of gipsies are very heavy drinkers. They consider it no disgrace foe either man or woman to be drunk, three fourths of the gipsy women are smokers and they are not particular as to the cleanliness of the pipe, or who has used it, there is a very fraternal feeling in this respect among them. They will quarrel like Kilkenny cats over a penny, but will kiss each other over a pipe.

The digestive systems are not over sensitive as to the kind of food they eat, hedgehogs are their dainty dishes, Mrs SMITH, a gipsy at Notting Hill, is anxious to have one cooked for me, and says I shall like it better than pheasant. This treat, I told her, I must let stand over for some time longer.

An English woman, the wife of a gipsy told me at the commencement of this year, that she had seen her husband "eat as many cooked snails as would fill a plate at one meal" Of course there are exceptions as among other classes. I have found good clean respectable industrious men and women among the gipsies, and worthy of a better calling, and Wish with all my heart there were more good ones among them. Things that an ordinary Englishman would throw upon the dung-heap, some of the gipsies will carry home to make soup of. Knuckle bones, obtained in many instances by fortune telling, are their general pot-boilers. The poor gipsy woman are as a rule the slaves and drudges for the whole family. In three cases out of four providing for the poor children rests upon the women.

I think I am speaking under the mark when I say there are not five out of every hundred gipsies who can read or write. No matter where I go or what encampment I visit, the same issue is everywhere manifest. I visited one encampment near to Wandsworth last January, and found only one out of 74 men, women and children who could read and write, and little it was because when I put paper before him he could not tell the difference between "Christian" and "Christmas" I have met with several women among the gipsies who have been Sunday School scholars, and can read and write, but even these are not teaching their children a single letter. There is at times much sickness among them, principally fever and smallpox, but their secrecy and flitting habits prevent detection.

In most every country in Europe without exception steps have been taken by the State to improve the conditions of the gipsies. The gipsy children are being educated, consequently the gipsies are settling down to an industrious and quiet life, but we, who ought to have been first to lead the way, have done nothing for them except to make it felony to be seen in their company, and to class them by law as vagrants and vagabonds.

My plan for improving their condition is by first bringing their tents and vans under the eye and influence of the sanitary inspector. Second, by the means of a school pass-book the gipsy children, canal-boat children, show children, and auctioneers children could receive a very fair education at the hands of the schoolmaster as they are travelling through the country, and might be made to conform to the requirements of the Sanitary Inspector. All the points mentioned I have dealt with fully with the work I have in the press, entitled, "Our Gipsies and Their Children."

George SMITH [of Coalville]

Leicester Chronicle, Mar 4th 1882

Our Canal children

To the Editor

Sir, - In the midst of the surroundings of canal life of various phases and hues at Paddington Basin, which to be fully realised must be seen. I came upon a few days since a poor boat girl of 10 winters, belonging to a registered boat, in charge of a big heavy boat horse with a foot that seemed at every step ready to crush the poor child into the mud upon the towing path, as they tramped along together. A few questions gently put elicited that she was born in the cabin, or dark floating cage, and that there were living in the cabin at the present time, father, mother and five brothers and sisters of various ages, not one of whom could tell a letter, except the little girl, and she had only attended a day school one week in her life, and during that one week, she remarked - with pleasure in her face, and fire in her eyes - "I learned my A B C," She further stated that she had, had, three more sister and brothers born in the cabin, one of whom - a big boy - was drowned in the "cut" some time since, and a sister of six years old died of fever last Whitsuntide in the boat cabin, and was carried, when cold, by her mother in her arms through the public streets to her aunt's. Just as she was in the midst of her pitiful tale, her father came "storming" along the towing path, the sight and sound of whom sent the poor girl into tears. With much persuasion, and a little tact, I turned aside the threatened vengeance, and on the poor girl sped, her way at the heels of the horse, shouting with a trembling, screaming voice "Come up."

If the Canal Boats Act of 1877 was made a living reality, in accordance with the amending Bill I am humbly promoting, instead of a dead letter, as is now almost the case, through a few faulty places in the Act of 1877, this and many thousands of cases, similar in many respects, would be impossible. In the midst of the Parliamentary chaotic confusion, which our legislators find themselves enveloped in law-making, by clouds of words, like swarms of flies, darkening the Council Chamber, "full of sound and fury" signifying something I do - and I am uttering the voice of thousands - most sincerely hope that the rescuing hands of the Government may be seen clutching the measure held out to them, and turn into law a Bill which will, without any increased cost or inconvenience to those interested, worth mention, by the means of saving the 40,000 poor canal children of school age from further degradation and misery, and life the salvators nearer to heaven. -

Your obedient servant, George SMITTH [of Coalville]

Welton, Daventry, Feb 23rd 1882

© 2011, all rights reserved to date